Have you ever thought about the strange world of spiders and their unique anatomy? These eight-legged creatures can both fascinate and scare us, but there’s one question you might not have thought about: Do spiders have tongues? Get ready to be surprised as we reveal the truth about spider tongues in this easy-to-understand blog. We will dive deep into the incredible anatomy of these arachnids. From how they eat to their amazing adaptations, we’ll explore the world of spiders and share 8 incredible facts that will change the way you see these amazing creatures!

Table Of Contents

- Do Spiders Really Have Tongues?

- How do spiders taste their food?

- Spider Mouthparts

- Spider Digestive System

- The Role of Setae in Spider Sensory Perception

- Spider Silk: A Surprising Tasting Tool

- The Evolution of Spider Feeding Mechanisms

- Comparing Spider “Tongues” to Other Arthropods

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Conclusion

Do Spiders Really Have Tongues?

Let’s get straight to the point: Do spiders have tongues? The short answer is no, not in the usual sense. Unlike humans and many other animals, spiders don’t have a muscular organ like the tongue we’re familiar with. However, this doesn’t mean they lack the ability to taste or process their food. In fact, spiders have developed unique adaptations that perform similar functions to our tongues in their own specialized way.

How do spiders taste their food?

Although spiders don’t have tongues, they do possess highly specialized structures that allow them to taste their surroundings and prey. These structures, known as “pedipalps,” are located near the spider’s mouth. Pedipalps are sensory appendages that help spiders detect chemicals and vibrations, functioning like a combination of taste buds and antennae.

Spider Mouthparts

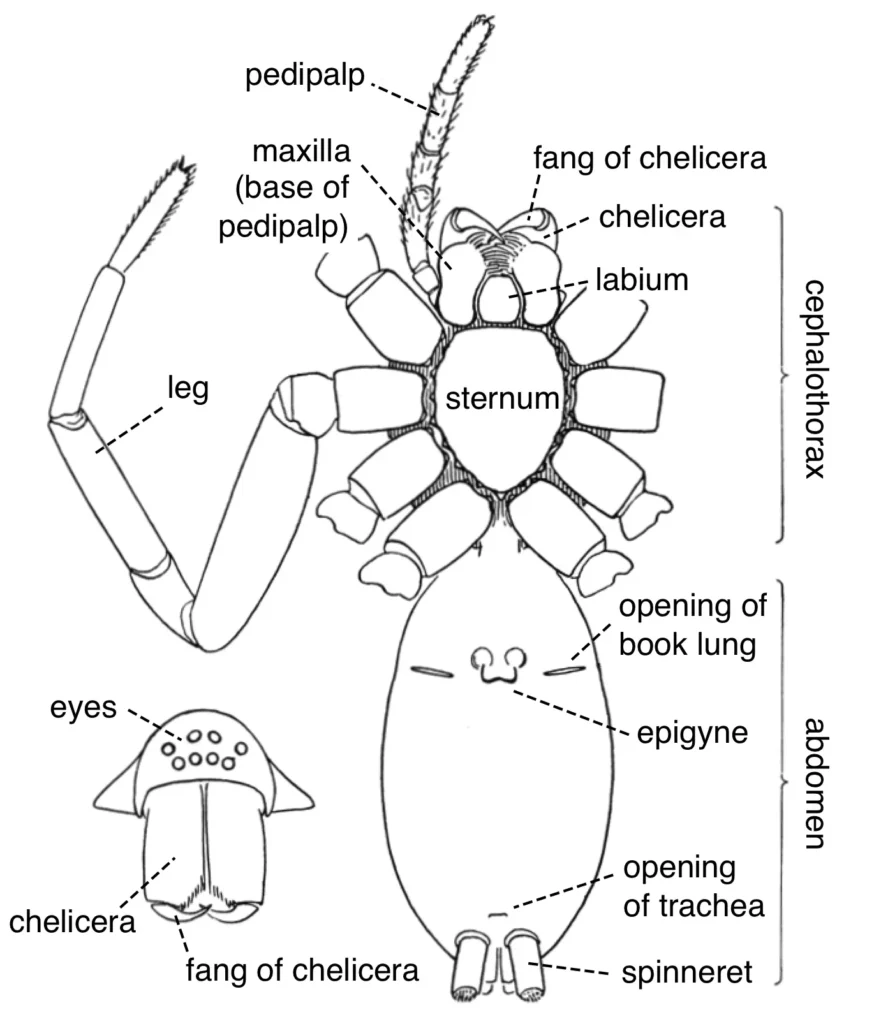

The underside and head of a female ecribellate entelegyne spider

To understand how spiders make up for not having a tongue, we need to look at their unique mouthparts. Spiders have a complex set of structures around their mouths, including:

- Chelicerae: These are the spider’s fangs, used to inject venom and grasp prey.

- Labium: A small, lip-like structure that helps guide food into the mouth.

- Endites: Plate-like structures that assist in handling, manipulating food and used to filter particles from the spider’s liquid diet.

Spider Digestive System

These mouthparts work together in a fascinating process of hunting and eating, allowing spiders to capture and process their meals effectively, even without a traditional tongue.

Spiders have an impressive digestive system that compensates for their lack of a tongue. Instead of chewing their food, spiders rely on a process called “external digestion.” Here’s how it works:

- The spider injects its prey with venom, which contains digestive enzymes.

- These enzymes start breaking down the prey’s internal organs, turning them into a liquid.

- The spider then uses its powerful sucking stomach to draw in this nutrient-rich liquid.

This method removes the need for a tongue to handle food inside the mouth, as the spider essentially drinks its pre-digested meal.

The Role of Setae in Spider Sensory Perception

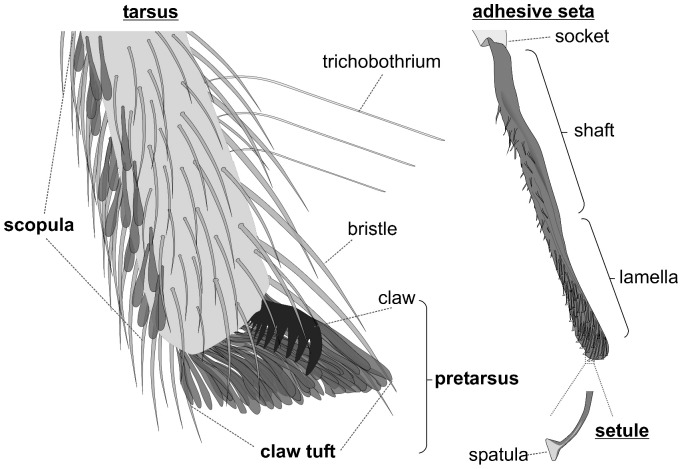

Another fascinating aspect of spider anatomy that relates to their ability to “taste” their environment is the presence of setae. These are fine, hair-like structures that cover much of a spider’s body, including the areas around its mouth. Setae are extremely sensitive and can detect:

- Chemical signals

- Vibrations

- Air currents

- Changes in temperature

These sensory abilities enable spiders to gather a vast amount of information about their environment and potential prey, offering insights far beyond what a simple tongue could provide.

Spider Silk: A Surprising Tasting Tool

Did you know that spider silk helps spiders perceive taste? Many spiders use their webs as an extension of their sensory system. When an insect gets caught in a web, the vibrations travel along the silk strands. The spider detects these vibrations through specialized organs in its legs called “slit sensilla.” The slit sensilla, also known as the slit sense organ, is a small mechanoreceptory organ or group of organs found in the exoskeleton of arachnids. This enables the spider to locate its prey, gather information about its size and movement, and even taste its environment, all without needing a tongue!

The Evolution of Spider Feeding Mechanisms

The absence of a tongue in spiders is a result of millions of years of evolution. Spiders have developed highly specialized feeding mechanisms that perfectly suit their predatory lifestyle. Some fascinating evolutionary adaptations include:

- Venom glands: Allowing spiders to subdue prey much larger than themselves.

- Silk production: Enabling the creation of intricate webs for catching prey.

- Sensitive hairs and organs: Providing detailed information about their environment.

These adaptations have helped spiders become one of the most successful groups of predators on Earth. As of November 2023, taxonomists have recorded over 51,673 spider species in 136 families.

Comparing Spider “Tongues” to Other Arthropods

While spiders may not have tongues, it’s interesting to compare their sensory and feeding structures to those of other arthropods:

- Insects: Many insects have a proboscis, a long, tube-like structure used for feeding.

- Crustaceans: Some crustaceans possess appendages called maxillipeds that help manipulate food.

- Centipedes and millipedes: These arthropods have structures known as gnathochilaria that assist in feeding.

This variety in feeding structures demonstrates the incredible adaptability of arthropods and highlights the unique evolutionary path that spiders have followed.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: If spiders don’t have tongues, how do they taste their food?

A: Spiders use specialized structures called pedipalps and sensory hairs to detect chemicals and vibrations, allowing them to “taste” their environment and prey.

Q: Can spiders eat solid food?

A: No, spiders cannot eat solid food. They use external digestion to liquefy their prey before consuming it.

Q: Do all spiders have the same mouthparts?

A: While the basic structure is similar, there can be variations in spider mouthparts depending on the species and their specific feeding habits.

Q: How do spiders know what’s safe to eat?

A: Spiders rely on their sensory organs, including pedipalps and setae, to detect chemical signals that indicate whether something is edible or potentially harmful.

Q: Can spiders taste things like humans do?

A: While spiders can detect chemicals, their sense of “taste” is quite different from humans. They are more attuned to detecting specific compounds that indicate the presence of prey or potential mates.

Conclusion

As we’ve discovered, the world of spider anatomy is far more complex and fascinating than we might have imagined. While these eight-legged wonders may lack traditional tongues, they’ve evolved an incredible array of adaptations that allow them to thrive as expert predators. From their specialized mouthparts and external digestion to their remarkable sensory capabilities, spiders have proven that there’s more than one way to taste and process food in the animal kingdom.

The next time you spot a spider in your garden or spinning its intricate web, take a moment to appreciate the millions of years of evolution that have shaped these remarkable creatures. Their unique adaptations, including their tongue-less feeding mechanisms, are a testament to the incredible diversity of life on our planet.

So, while we can definitively say that spiders don’t have tongues in the conventional sense, their alternative sensory and feeding structures are no less impressive. These adaptations have allowed spiders to become one of the most successful and diverse groups of predators on Earth, playing crucial roles in ecosystems worldwide.

As we continue to study and learn about these fascinating creatures, who knows what other surprising discoveries await us in the world of spider biology? One thing is certain: the more we uncover about these eight-legged marvels, the more we realize how much there is still to learn about the intricate and awe-inspiring world of nature that surrounds us.

Resources

By Original: James Henry EmertonDerived: Peter coxhead – This file was derived from: Spider external anatomy.png:The image was re-labelled using current terminology, without the leg parts, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58568020

Wolff, Jonas & Nentwig, Wolfgang & Gorb, Stanislav. (2013). The Great Silk Alternative: Multiple Co-Evolution of Web Loss and Sticky Hairs in Spiders. PloS one. 8. e62682. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062682.

“What a gem I’ve discovered! The thoroughness of your research combined with your engaging writing style makes this post exceptional. You’ve earned a new regular reader!”

Thank you! Keep reading:)

“Thanks for sharing such valuable information!”

Thank you! Keep reading:)